Puppetry as an art form has a rich history in many cultures around the globe. Aside from the distinct styles of puppetry present in many Native American tribes, American puppetry is primarily descended from British marionette puppetry.

In the United States, puppetry began with itinerant performers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including John Durang in 1786: “using figures about two feet high, he performed The Poor Soldier on a stage with a curtain, scenery, lamps, and chandeliers… to crowded houses every night.”[1]

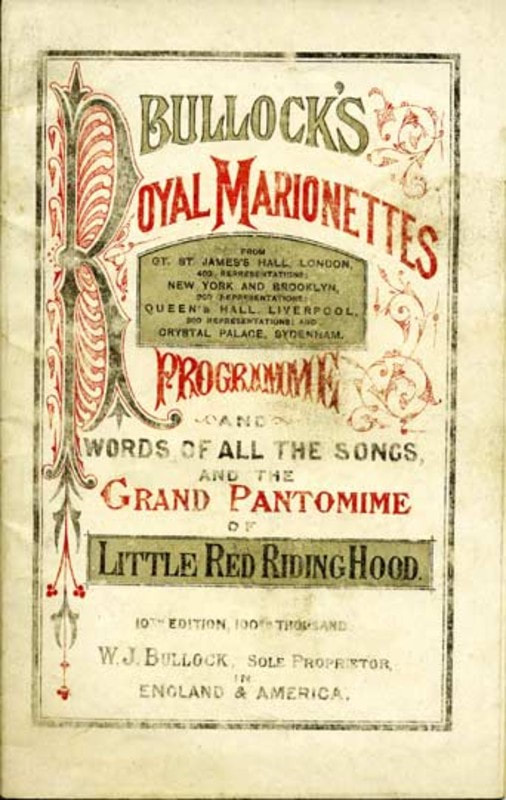

The Royal Marionettes, later renamed to the Anglo-American Marionette Combination, had an extravagant (though problematic) traveling show that cemented puppetry as an American art form. “Their program opened with a variety act composed of traditional comic antics: tightrope walkers, contortionists, Irish dancers, and a chorus of Chinese bell ringers. A minstrel show followed that replicated in miniature live shows then widely patronized… The major section of the evening offered a marionette version of the great musical hit of the 1860s, The Black Crook.”[2] In more ways than one, this and other traveling puppet troupes presented a microcosm of the existing entertainment landscape. Puppetry also existed inside that existing landscape, with puppeteers and ventriloquists often appearing in vaudeville shows.

In the United States, puppetry began with itinerant performers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including John Durang in 1786: “using figures about two feet high, he performed The Poor Soldier on a stage with a curtain, scenery, lamps, and chandeliers… to crowded houses every night.”[1]

The Royal Marionettes, later renamed to the Anglo-American Marionette Combination, had an extravagant (though problematic) traveling show that cemented puppetry as an American art form. “Their program opened with a variety act composed of traditional comic antics: tightrope walkers, contortionists, Irish dancers, and a chorus of Chinese bell ringers. A minstrel show followed that replicated in miniature live shows then widely patronized… The major section of the evening offered a marionette version of the great musical hit of the 1860s, The Black Crook.”[2] In more ways than one, this and other traveling puppet troupes presented a microcosm of the existing entertainment landscape. Puppetry also existed inside that existing landscape, with puppeteers and ventriloquists often appearing in vaudeville shows.

|

A program for a performance of the Royal Marionette's extravaganza entitled Little Red Riding Hood.[3]

|

Tony Sarg was another major player in early puppetry; his 1916 production of A Night in Delhi with complex puppets, and an insistence on “strong scripts and able speakers in order to give full dramatic effect to performances” earned his company, and puppetry in general, a spot on Broadway.[4]

Puppetry grew to have such a strong hold on the American entertainment industry that the Federal Theatre Project introduced Marionette Units to employ out-of-work puppeteers during the Great Depression. During this time, “the FTP had more puppeteers working in New York City alone than had been employed previously throughout the country.”[5]

Bil Baird was a prominent puppeteer of the twentieth century who greatly shaped the field with his belief that “the figure must possess form and sound that communicates its creator’s intentions because the puppet is an extension of the puppeteer.” [6]

Puppetry reached even broader audiences with the advent of television, with programs such as Kukla, Fran and Ollie; Howdy Doody; and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood bringing puppets into the American living room.[7]

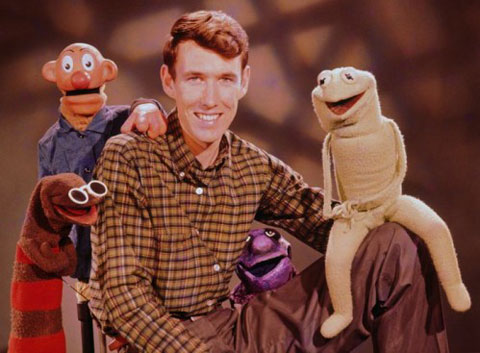

Perhaps the most important of television’s puppets, however, were Jim Henson’s Muppets. Henson “combined marionettes and puppets, but no longer confined them to traditional stages or to conventional sizes,”[8] proving that puppetry was suitable entertainment for all ages, not only for children. The Muppets were so successful in part because they took advantage of the available technology; they were “designed for television from the start. [Henson] was not taking a style developed for live theatrical performances and adapting it to television; rather, television was his stage.”[9]

Puppetry grew to have such a strong hold on the American entertainment industry that the Federal Theatre Project introduced Marionette Units to employ out-of-work puppeteers during the Great Depression. During this time, “the FTP had more puppeteers working in New York City alone than had been employed previously throughout the country.”[5]

Bil Baird was a prominent puppeteer of the twentieth century who greatly shaped the field with his belief that “the figure must possess form and sound that communicates its creator’s intentions because the puppet is an extension of the puppeteer.” [6]

Puppetry reached even broader audiences with the advent of television, with programs such as Kukla, Fran and Ollie; Howdy Doody; and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood bringing puppets into the American living room.[7]

Perhaps the most important of television’s puppets, however, were Jim Henson’s Muppets. Henson “combined marionettes and puppets, but no longer confined them to traditional stages or to conventional sizes,”[8] proving that puppetry was suitable entertainment for all ages, not only for children. The Muppets were so successful in part because they took advantage of the available technology; they were “designed for television from the start. [Henson] was not taking a style developed for live theatrical performances and adapting it to television; rather, television was his stage.”[9]

|

Jim Henson's Muppets, part-marionette, part-puppet, were featured in numerous television series and films.[10]

|

|

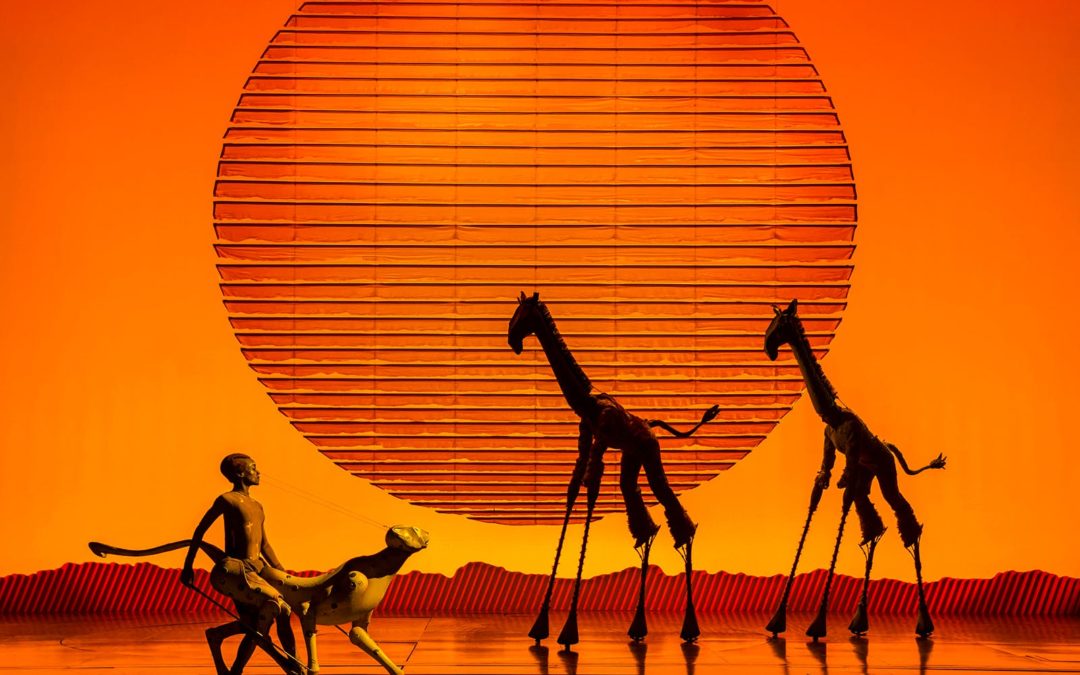

While puppetry flourished in television and film, the form did not completely abandon live theatre, and several recent productions make extensive use of puppetry.

In The Lion King, designer Julie Taymor incorporates numerous styles of puppetry from around the world, including Japanese bunraku, Indonesian wayang, along with other shadow puppets, rod-and-string puppets, and hand-manipulated dolls, enriching the existing American tradition.[11][12] |

|

Avenue Q borrowed extensively from the Muppets and Sesame Street in its puppetry style, in a satire with thick layers of irony. These “sophisticated variations on the sock puppet” interact eye-to-eye with human characters, without calling attention to the anatomical difference between them.[13] The show’s adult-oriented humor can be traced to other antecedents within the form of puppetry, including the Yale Puppeteers, who specialized in original “satirical material in songs and sketches” directed at adult audiences beginning in 1923.[14][15]

|

Puppetry is present in Sagittarius Ponderosa in the form of Peterson, a puppet who magically falls from above to be manipulated by one of the actors already onstage. Peterson’s design is not clearly defined within the script, but the puppet’s nonchalant style of interacting with the other characters is clearly descended from Avenue Q and by extension other forms of American puppetry. However, a particular production may choose to draw inspiration for the puppet’s design from other sources.

Notes

[1] Lowel Swortzell, “A Short View of American Puppetry,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 24.

[2] Swortzell, 25.

[3] “Bullock’s Royal Marionettes Programme.” Photograph of historical document. World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts, https://wepa.unima.org/en/bullocks-royal-marionettes/#prettyPhoto.

[4] Swortzell, 26.

[5] Swortzell, 28.

[6] Swortzell, 28.

[7] Swortzell, 31.

[8] Swortzell, 31.

[9] Leslee Asch, “Exhibitions and Collections of the Jim Henson Company,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 240.

[10] The Jim Henson Company. “Jim Henson on the Set of ‘Sam and Friends.’” Photograph. Daily News, https://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/tv-movies/kermit-frog-grew-minor-character-iconic-muppet-57-years-article-1.1075021.

[11] Alan Woods, “;’Bringing Together Man and Nature:’ The Theater of Julie Taymor,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 226.

[12] Joan Marcus. “The Lion King.” Photograph. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2017/10/29/560292712/bold-experiment-turned-broadway-hit-lion-king-continues-to-thrill-and-heal.

[13] Ben Brantley, “Theatre Review; A Feeling You’re Not On Sesame Street,” New York Times, August 1, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/01/movies/theater-review-a-feeling-you-re-not-on-sesame-street.html.

[14] Swortzell, 28.

[15] Sara Krulwich. “Avenue Q.” Photograph. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/10/theater/avenue-q-musical-closing.html.

See a complete bibliography here.

[1] Lowel Swortzell, “A Short View of American Puppetry,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 24.

[2] Swortzell, 25.

[3] “Bullock’s Royal Marionettes Programme.” Photograph of historical document. World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts, https://wepa.unima.org/en/bullocks-royal-marionettes/#prettyPhoto.

[4] Swortzell, 26.

[5] Swortzell, 28.

[6] Swortzell, 28.

[7] Swortzell, 31.

[8] Swortzell, 31.

[9] Leslee Asch, “Exhibitions and Collections of the Jim Henson Company,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 240.

[10] The Jim Henson Company. “Jim Henson on the Set of ‘Sam and Friends.’” Photograph. Daily News, https://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/tv-movies/kermit-frog-grew-minor-character-iconic-muppet-57-years-article-1.1075021.

[11] Alan Woods, “;’Bringing Together Man and Nature:’ The Theater of Julie Taymor,” in American Puppetry: Collections, History, and Performance, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 226.

[12] Joan Marcus. “The Lion King.” Photograph. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2017/10/29/560292712/bold-experiment-turned-broadway-hit-lion-king-continues-to-thrill-and-heal.

[13] Ben Brantley, “Theatre Review; A Feeling You’re Not On Sesame Street,” New York Times, August 1, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/01/movies/theater-review-a-feeling-you-re-not-on-sesame-street.html.

[14] Swortzell, 28.

[15] Sara Krulwich. “Avenue Q.” Photograph. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/10/theater/avenue-q-musical-closing.html.

See a complete bibliography here.

Photo used under Creative Commons from Sharon Mollerus